So I realize I haven’t posted in a while and that’s because I’ve been working on a quite long philosophy post. So I’m going to start a new short series called Penny Thoughts! It’ll cover famous thought experiments, paradoxes, and well-known philosophical concepts. And today we’re going to discuss a classic: The Fermi Paradox.

Who is Fermi?

For anyone that has seen Oppenheimer, they may have heard of the name Fermi during the film. Enrico Fermi was an Italian physicist best known for spearheading the construction of the first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1, as part of the Manhattan Project. The Manhattan Project was a program led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada to create nuclear weapons during World War II.

It was during the project, in the summer of 1950, where Fermi accidentally created his paradox by stating: “But where is everybody?” The everybody he was referring to are aliens or intelligent life on other planets.

What is the Fermi Paradox?

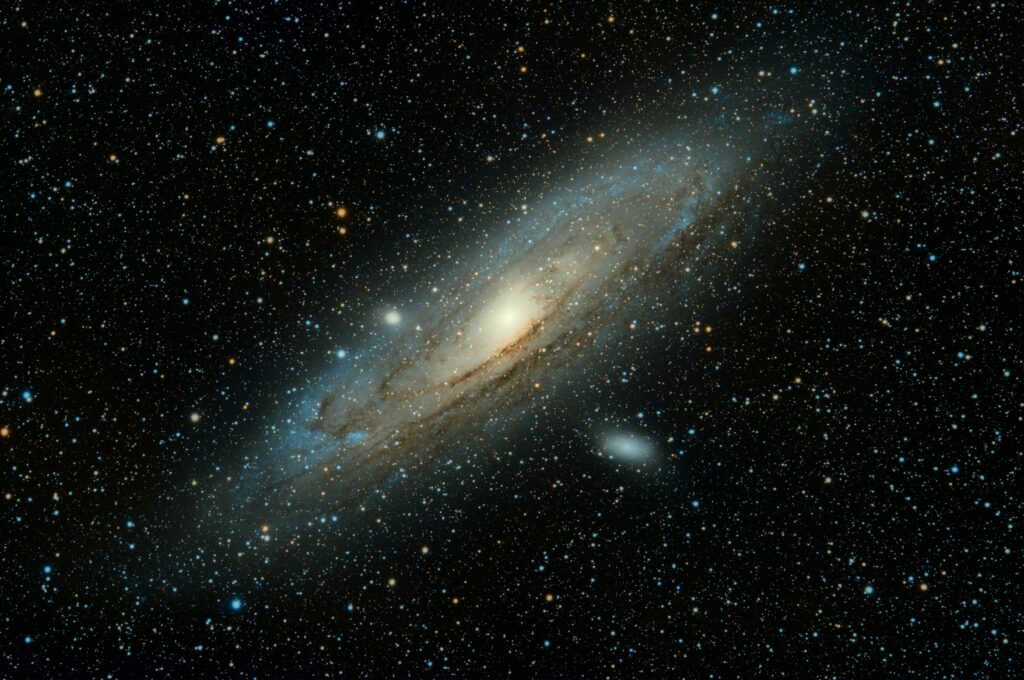

To break down why it’s paradoxical for us humans to have not found other intelligent life, we need to first understand how big our galaxy is:

- In our galaxy, the Milky Way, NASA predicts there are around 100 to 400 billion stars. About 20%, or at least 20 billion of them, are similar to our Sun.

- There are around 300 million to 40 billion Earth-like planets within the Goldilocks zone. The Goldilocks zone is a habitable zone that can support the existence of water in a liquid state. Planets that are too close to a star, such as Mercury, would cause the water to evaporate, and planets that are too far, such as Neptune, would only have ice. So, if we take 20% of these 300 million planets to account for Earth-like planets around a Sun-like star, we have at least 60 million planets.

- Our universe is 13.7 billion years old, but the universe has only been cool enough to support life in the last 10 billion years. Our sun is about 4.57 billion years old, which means it’s possible for other intelligent life to have existed on other planets before us.

- Given how many billions or millions of years other intelligent life had before the human race, it’s possible at least one of them achieved interstellar travel. This is considering the slow pace it would take us to accomplish such a feat, currently clocked in about 5 to 50 million years given our current technology.

So, assuming steps 1 through 4 did occur at any point, why haven’t aliens visited us yet?

Possible Solutions

The first proposal is the Rare Earth hypothesis. It states that although millions of Earth-like planets around Sun-like stars with water exist, the Earth is unique in that its climate was stable enough for long enough to support the development of life.

In the universe, hundreds of things could happen to a planet that would impede the development of life: the climate becomes too cold, a meteor wipes out all life, or a star could die and become a black hole that destroys the planet. The Earth, and by consequence we, are lucky enough to not only have some life survive both the Ice Age and the meteor that wiped out the dinosaurs, but also dodge cosmic disasters like supernovas.

However, there is no proof that the Earth is unique since our sample size of life existing on planets is just one. According to the mediocrity principle, our planet is just one of millions of similar planets. It just so happens, due to chance, that this one was able to create and sustain life.

The second theory, the Unobservable Life hypothesis, proposes that aliens do and have existed, or they existed and then perished millions or billions of years before humanity came into existence.

Due to life being able to exist at any point in the last 10 billion years, it’s possible that intelligent life can come and go with millions or even billions of years in between each other. Or that even if two or more alien civilizations were to be in existence simultaneously, that they would be too far to even notice each other. Life might exist, but it would be outside the range of our space probes and communication signals.

A simple refutement is that there is no proof that this is the case. It is merely conjecture and there is no convincing reason for us to believe in this hypothesis over other hypotheses. For people who support this theory, they must bear the burden of proof.

Lastly, we have the Dark Forest hypothesis. Similar to the previous theory, intelligent life does exist but chooses to deliberately remain hidden using their advanced technology from other forms of intelligent life.

The first counterargument comes from American astrophysicist Neil DeGrasse Tyson. He argues that given all the varied amounts of life on Earth, only one species has ever reached what we consider true intelligence: ourselves. This fact is even more shocking if you take into account that over the last 4 billion years that organisms have existed on Earth, over 99% of all species have gone extinct. Based on the statistics, advanced intelligence may not be a necessary evolution for life. If so, then there is no intelligent life with the capacity to hide from us.

The second counterargument by British physicist Brian Cox proposes that, given humanity over the centuries, it is not in the nature for intelligent life to hide. Rather, it seems natural for them to want to conquer and own the belongings of others. Alternatively, maybe a compulsion to own might result in an evolutionary process that bestows advanced intelligence? Regardless, if it is in the nature of sufficiently intelligent beings to covet things, then hiding would go against their being.

The Great Filter

The last possible solution, which I think is the most likely, is known as the Great Filter. The Great Filter theory states that there are barrier(s) that impede the creation, development, or progress of life.

According to Robin Hanson, a professor of economics, there are nine steps in evolution for life to rule its observable universe: 1) The right star system, 2) Reproductive molecules, 3) Simple single-cell life (viz. prokaryotes), 4) Complex single-cell life (viz. eukaryotes), 5) Sexual reproduction, 6) Multi-cell life, 7) Tool-using animals with intelligence, 8) A civilization advancing toward the potential for a colonization explosion, and 9) Colonization explosion.

In regards to what a colonization explosion is, there is something known as the Kardashev Scale which determines a civilization’s technological advancement given how much energy it can utilize. A Type I Civilization would be able to harness all the energy on its planet, such as geothermal steam, winds, and tides. Humanity is currently estimated to be between 70 and 80% of reaching this goal. A Type II Civilization would be able to harness the energy of its own star. Although not currently feasible, it is theorized to be possible. One such option is the Dyson sphere. Finally, a Type III Civilization would have control over and be able to harness all the energy in its own galaxy.

So, given Hanson’s nine steps it’s possible that humanity is one of the first, if not the first, civilization to pass the great filter(s). We may be the only intelligent life because life was able to exist, reproduce, evolve to be multicellular organisms, and gain intelligence over time! However, it’s possible that instead of us passing these barriers, the barrier to all life instead sits before us in our future.

If we look toward the Unobservable Life hypothesis again and assume that other aliens did die long ago, maybe what killed them was a situation fabricated of their own doing. Looking at our history, we could go extinct due to conflict-related self-genocide (e.g. nuclear or biological weapons) or neglect of our environment (e.g. climate change). It’s possible these were problems aliens before us encountered and were unable to overcome. If that’s the case, then we have a duty to gather together and overcome our extreme differences to save ourselves. Because if it is the case that we are the only intelligent life in the universe, the moment we destroy ourselves is the moment we extinguish all life, potentially forever.

“I believe every human has a finite number of heartbeats. I don’t intend to waste any of mine.”

~ Neil Armstrong