The Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3

Quick spoiler alert! The media I’m going to be mentioning includes the Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3, the Sweet Tooth comic book (although I do highly recommend the Netflix television show as well), The Promised Neverland, and Brave New World (again also recommend the Peacock television show). If you have not watched or read these yet, I suggest you do first because I will be discussing minor parts of their plot during the article.

Also, before I forget, I will be using some pictures of animals that a majority of people will find disturbing.

Animals in the Human Kingdom

So, I saw Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3 two weeks ago, and I think it was a difficult film to watch. Notably, the parts where Rocket’s friends were captured, experimented on, and ultimately killed in order to benefit complete strangers. Rocket does escape, but he’s been literally transformed by his experience as a lab rat (raccoon? trash panda?) under the High Evolutionary’s scientific gaze. What I found simultaneously amusing and horrifying was watching a film showcasing animal cruelty at the hands of “higher beings” whilst surrounded humans eating hot dogs, pepperoni pizzas, and hamburgers. If we all sympathize with the plight of animals, then why do we directly and indirectly support industries that engage in such practices?

In the cosmetic industry it’s commonplace to perform the Draize rabbit eye test. Rabbits, due to their lack of tear glands, have various chemicals dripped into their eyes to determine if they are an irritant. Most of them end up going blind and are then killed because they are no longer useful.

From an educational standpoint, it’s found that at least 75% of the North American population will have dissected at least one rat or frog during their science classes. Speaking of science, it’s well known that across the globe animals are used for medical research. Currently, zebrafish are used to study the real-time causes and effects of cancer. This is due to their high breeding rate, and how they can develop cancer quite easily via forced genetic mutation. Even if we were to argue that some of us don’t use cosmetics, have never dissected an animal, or benefitted from such medical research, we still have to question our diets.

Recently, there was a statistic that states over 85% of the humans on Earth include meat in their diet. Cows and chickens and pigs are cramped inside small, enclosed quarters. The lucky ones get to live in squalid conditions amongst their brethren to continuously create resources for us humans to enjoy: milk and eggs and future offspring for us to repeat the process against. The unlucky ones, those unable to create such resources, are systematically slaughtered, have their remains loaded onto a truck, and are sold for our consumption. For the remaining vocal minority of us that have plant-based diets, have you seen the items within your house?

Some things that my family uses include Jell-O made from protein in animal skin and bones, beer containing chemicals found in fish bladders, red food dye crushed out of red beetles, soap bars made of animal fat, dry dog food derived from pork, perfume taken from beaver glands, nail polish manufactured with fish scales, plastic bags made of “slip agents” from animal fat, crayons also made of melted animal fat, boiled animal glue, cowhide leather, and violin strings which are stretched sheep and goat intestines. There are many more items I could name, but this article would go on forever.

Now that we all know we are at fault for using items, convenient but fatal to animals, should we continue doing so? Well, the question is: Is it morally permissible for humans to harm or kill non-human animals?

Applied Ethics Terminology

Before we address the literal elephant in the room, I need to break down some fancy philosophy terms I will use going forward:

- Moral status means that a thing counts for us morally. For example, I cannot punch my son because he has moral status, but I can punch a rock because it lacks moral status.

- Moral consideration means that something has moral status. Going forward, a thing having moral status and a thing being worthy of moral consideration are synonymous, and I’ll use them interchangeably.

- Moral agents are things that have moral status, can tell the difference between morally right and wrong (see below for their descriptions), and are held accountable for those actions. So I, an adult human, am a moral agent, but I would not expect my pet dog to be a moral agent.

- Moral patients are things that have moral status but cannot tell the difference between morally right and wrong and/or cannot be held accountable for those actions. My pet dog, my infant son, or my senile relatives are moral patients.

- Morally right (i.e. moral) actions are actions we would consider good. My definition is very vague because of how abstract the idea is, but it’s easy to see in practice. Giving money to the homeless, donating blood, or refusing to participate in bullying are all moral actions.

- Morally wrong (i.e. immoral) actions are actions we would consider bad. Again a loose definition, but we all identify murder, rape, and refusing to help a drowning child as immoral actions.

- Morally neutral actions are actions that are neither moral or immoral. So, me putting back cereal on the shelf and buying apples are morally neutral.

- Moral permissibility has different definitions depending on which type of ethical theory you believe in (e.g. utilitarianism, deontology, contractualism, etc.), but for this article I will define it as actions that are morally right or neutral.

- Moral impermissibility will be used to describe actions that are morally wrong.

- Moral obligations are moral actions that are required. Going back to my drowning child example, we are morally obligated to save the child (assuming we can all swim) and not saving the child is considered morally impermissible.

- Lastly, moral justification means a moral agent performs an action with good moral reasoning. To illustrate, if I choose to help my neighbor by fixing their sink, I am morally justified in thinking that my action is morally right and will benefit my neighbor. Additionally, I can also exercise my moral justification by weighing moral decisions, such as deciding if I should donate my money to a homeless person or a non-profit organization.

With all that jargon out of the way, we can now move forward with the question: Is it morally permissible for humans to harm or kill non-human animals? Also feel free to keep referring back to this section as much as you like. Honestly, I have a four-year degree in philosophy, and I still had to refresh myself on most of these definitions.

Animal Testing

The COVID 19 outbreak happened over three years ago, and we are still feeling its effects. However, it has gotten to a point where our daily lives have become normal again: Workers going back into the office, students taking live classes, and being able to attend parties, concerts, and movie theaters. This is all thanks to proper sanitization practices (e.g. washing our hands or using hand sanitizer), wearing protective measures (e.g. face masks or shields), and getting vaccines. But what were the costs for the vaccine?

Researchers around the world used a variety of animals based on how closely COVID 19 manifested in their species compared to humans. These include Syrian hamsters and non-human primates. Additionally, some animals were genetically manipulated to mimic human symptoms or to have the capability of even receiving the virus. Mice were not able to get COVID 19 due to a protein they differ from humans, so some of them were genetically modified in order to transmit the virus to them. There is no accurate recording as to how many animals were raised in captivity, captured for experimentation, used for testing, or were killed during the process. Yet I imagine it must number in the thousands considering how expedited the vaccines were after the virus broke out, and I don’t see anyone mentioning it.

Every day I hear about people outraged over animal testing in the cosmetic and educational sectors, but not many over animal testing in the medical industry. I’m not saying cosmetics and education are not doing terrible things to animals, but in what way are they more at fault? It really comes down to an argument for need. We don’t need cosmetics, so we don’t need to test them on animals. Likewise, we don’t need to dissect animals because we could mimic the process (e.g. donated human cadavers) or simulate them without harm (e.g. watching a video or, in the future, using VR). However, there is a medical need.

There is a popular variation of the Trolley Problem by Philippa Foot where there are five patients in a hospital requiring emergency transplant surgery for various organs, and if they don’t get it soon then they will all die. There are currently no organs available in the hospital, but the doctors could go out into the street, kidnap a person, kill them, take their organs, and save the five patients.

Utilitarianism, an ethical theory that espouses that morally right actions are actions that maximize pleasure and minimize pain, would say that killing the person is a moral action. That’s because one person was killed in order to save five. However, I don’t think any of us would propose that as a moral action at all, and we would all agree that it is morally wrong to do that. I won’t go into too much depth about why we think that, but it has to do with how we are trespassing on personal rights, namely a right to life, or how we are treating the five patients as more worthy of moral consideration than the killed person. Regardless, randomly killing people to save strangers in a hospital is not a practice human society condones.

To set some ground rules for the previous hospital argument, it is immoral to kill one human to save any number of humans. There will be some disagreement because of edge cases like one person offering their life to save the rest of the Earth’s population, or a soldier drawing fire so their platoon can retreat. Nonetheless, this argument is outside the scope of animal rights so we’ll go with the previous assumption. So, assuming it is wrong to have doctors kill even one person to save any number of people, why is it okay to have researchers kill one animal to save any number of people?

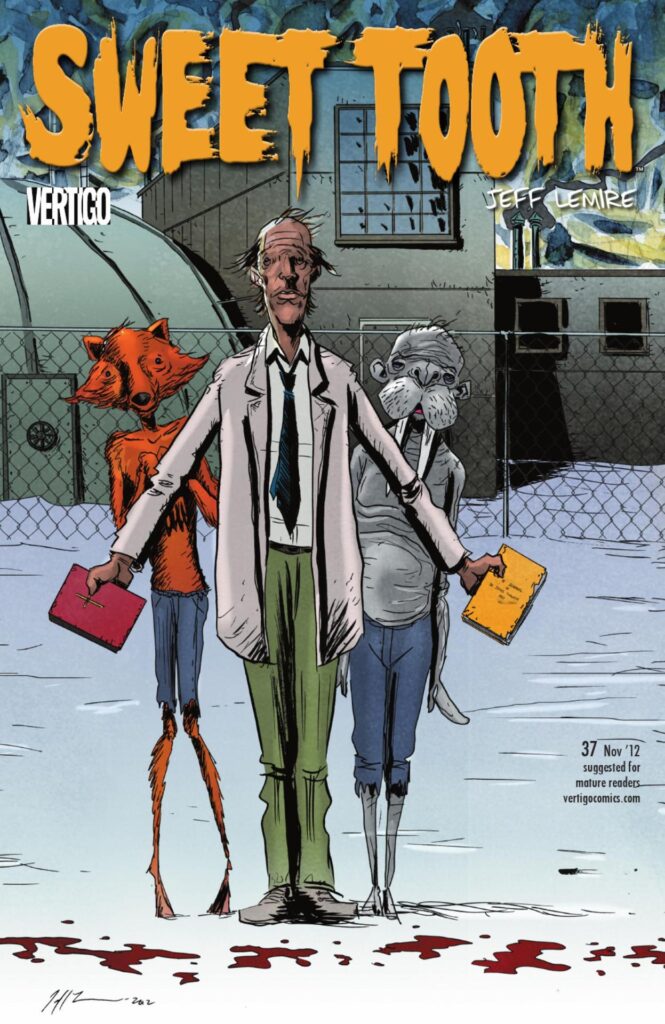

Sweet Tooth Vol. 2: In Captivity

The argument for need that people hold is that medical research is necessary in order to prevent human deaths, and if it’s wrong to kill humans then it’s also wrong to perform painful tests on them as well. Therefore, the only alternative is animals. But, in the Sweet Tooth comic book a viral pandemic (how ironic) kills a majority of humans, and the following generation from the survivors are all hybrids of humans and one other animal. Gus, the main character, is a boy with deer-like features, such as antlers and long, pointed ears. In the second issue, In Captivity, he finds himself in a facility that performs tests on pregnant women and hybrid children to find a cure in order to create entirely human babies. Additionally, the facility ends up torturing and killing a majority of their test subjects. It’s obvious to see that Gus is not a human, but we feel sympathy for him and the other hybrid children when they are used for experimentation. If we think it’s innately wrong that humans should be used for testing and that half-human half-animal hybrids are also used for testing, then why can’t it be morally wrong for animals to be used for testing?

Jumping back to Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3, we notice that animal testing feels wrong when we are confronted with it. Granted, the movie presents a fictional account where the animals are given sentience and are physically transformed via a combination of amputations and cybernetic enhancements. But how is Teeths the walrus having his eyes forced open not dissimilar to the process of the Draize rabbit eye test? How is Lylla the Otter’s robotic limbs not a step away from the modern cyborg fish (please Google it)? How far removed is mutating Rocket the raccoon into a bipedal, humanoid shape from genetically modifying mice? All of the fictional experiments feel so far removed from our reality, but how many years will it take to become a possibility and when will humans draw the line at such animal testing?

Raising Animals for Food

Just to get it out of the way, is not having a plant-based diet (i.e. being vegan) immoral? The human diet has been shown in practice to survive without consuming meat (along with milk, eggs, honey, etc.). The reason we eat steak, sushi, and ice cream are because we want to, not that we need to. So from that perspective, it is immoral. Just because I want money doesn’t mean I should steal from people. Us wanting something badly doesn’t morally justify every possible action we could take. However, there are some arguments the non-vegans could consider.

- As a human, I think it’s alright to eat animals. Out in the wild, predators (e.g. bears) eat prey (e.g. salmon). I, being an intelligent predator, am allowed to eat prey. This is a very speciesist way of thinking. Speciesism, a term coined by Richard Ryder, is the thought or practice of discriminating based on species. So, if you think the above, then you are speciesist, specifically one that places human lives over the lives of all other non-human animals. But maybe that’s alright?

A majority of us, including myself, are speciesist to varying degrees. I am a cat person, so I would be more likely to buy a cat as my next pet, as opposed to a dog, a fish, or a bird. That makes me a speciesist that prefers humans and cats over other animals. Close friends I know are scared of big dogs, such as Pitbulls. They are speciesist because they think small, cute dogs (e.g. Malteses) should not be euthanized, but bigger dogs should be because they seem more aggressive. Even if for the rare minority of us that think we have no preferential treatment for any animal, can you really say that you’d be willing to stop animal testing for king cobras? Do you really think tarantulas are as cute and fluffy as bunnies? How about coexisting with that wasp nest sitting outside your front door instead of calling the exterminator?

- Carl Cohen argues that all species seek to be the apex predator, and the apex predator has the right to protect itself by any means necessary. So, humans should be allowed to cage, torture, and even kill animals in order to remain at the top. He further states that non-human animals lack moral rights because they do not live in a moral world. A moral world, or a world constructed and governed by morality, is a purely human concept that is only applicable to the species that created it.

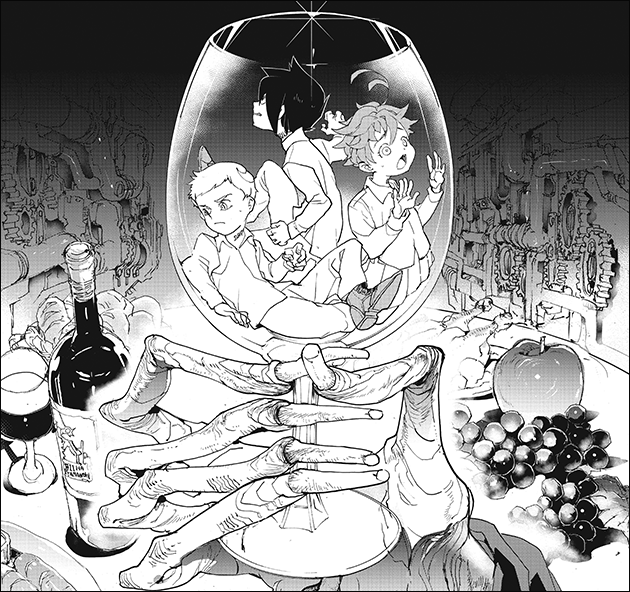

The above argument may seem compelling, but it hinges on the fact that humans are in charge. In The Promised Neverland, there is a fictional world full of orphanages. These orphanages exist on beautiful, fertile land that allow the children freedom to roam and play. The children are given comfortable clothes, soft beds, nutritious food, and a basic education. Little do the children know, they are being raised for food for a race of demons that exist above humanity. This really puts into perspective the open ranges of Vital Farms, or the massaging of Wagyu beef cows in order to relieve their stress. If the world in The Promised Neverland was actually a reality, humans would be in an uproar, and we would hear from our demon overlords that they are the apex predator and deserve to do anything to keep all other animals from taking their spot. Does Cohen’s argument for the superior species sound all that good when humans are lower than first place?

- The last argument I want to mention follows this logic. A family is driving down a dark country road when they suddenly hit a deer. The deer has been killed but it was not the family’s intent to kill it. Is it morally permissible for the family to eat the deer roadkill? Well, if buying meat is wrong because it indirectly supports the killing of animals, then me eating animals that have died from other causes is alright.

There’s a couple of problems with the previous logical conclusion. Firstly, if the family had hit and killed a human, then it would be immoral and taboo for them to eat said human based on that reasoning. Secondly, even if we all keep non-human animals in the conversation, the argument falls apart even under the slightest scrutiny. To illustrate, my family and I have a Himalayan Persian cat named Blue. Down the line in maybe ten to fifteen years, Blue will die of natural causes. When that happens, is it morally permissible for my family and I to eat her? She did not die because we wanted to kill her, rather we want to eat her because there is a moral justification, and it would be a waste of meat. Additionally, eating her does not cause her any pain because she’s already dead. Maybe the uneasiness of eating a dead pet has something to do with a respect for the dead that all cultures share, but if that was really the case then fast food restaurants across the country should be akin to places of worship. I don’t see people praying and thanking the cow for giving its life before buying a Big Mac.

Other Philosophers’ Stances

So, I’ve basically teased the idea of answering the question: Is it morally permissible for humans to harm or kill non-human animals? Unfortunately, there are no clear-cut answers to it because most philosophical questions create a variety of answers, but I thought it would be interesting to discuss other philosophers and their stances on the topic.

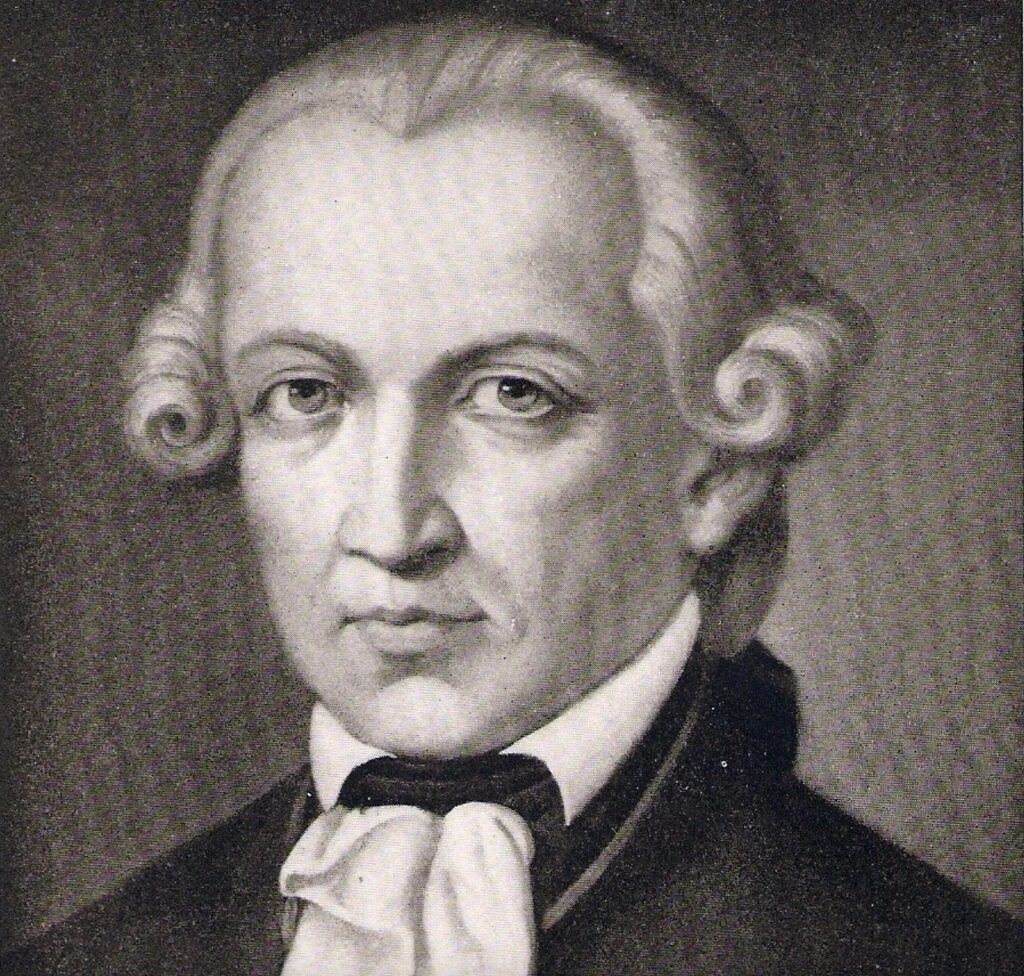

Immanuel Kant would say that it is morally permissible. To him, only humans have moral status because our rationality gives us the autonomy to make moral decisions. Animals make decisions based on instinct, but humans are able to push down such desires (e.g. sex, money, drugs, etc.) in order to live morally. However, he does mention that animals have indirect moral consideration because humans performing unnecessary actions against them (e.g. whipping dogs) damages those humans’ moral standing and the ability to make moral judgements. In short, if I get into the habit of kicking every dog I see, it might transform me into a person that thinks it’s natural to kick anything, such as children or the elderly.

An obvious counter argument comes from humans with marginal cases. We don’t consider babies, senile grandparents, or humans with mental disabilities to be rational all the time. As I mentioned near the top, these are cases of moral patients rather than agents. If the only determining factor for moral status was our intelligence, then we would have to agree that those people are not worthy of moral consideration. Thus, we could be morally justified in doing any type of act against them.

Some philosophers have found a way out of this argument by stating that those types of people, while lacking in rationality, have either the potential for it or are part of a species where the majority of its participants are rational. Shelly Kagan proposed an idea where moral status comes in degrees rather than being a binary “you have it or don’t have it” option. Thus, humans would have the highest moral status, the marginal case humans would have the second highest moral status, and all other animals would have varying statuses that rank lower than humans. The rub comes from how to determine how much moral status a species and its marginal cases would have. Do we farm cows because they have a lower moral standing than dolphins and tigers? Do endangered species earn a higher moral status than non-endangered species? Does LeBron James have a higher moral standing than us because he’s famous? While interesting, Kagan’s idea is fraught with questions and the assignment of moral degrees seems arbitrary at face value.

I think the final nail in the coffin for separating humans and animals by rationality is shown in Brave New World. The book explores a dystopian society where humans are genetically bred with a set amount of intelligence with the intent to fill specific jobs based on need. Furthermore, because the society places heavy emphasis on your job being tied to your intelligence, a hierarchy evolves where the most intelligent rank over the least intelligent. As the story continues, it’s found that characters of various backgrounds (Bernard Marx being an outcast in the highest class, and John, a “savage” raised with minimal intelligence) are deeply unhappy with the world and their lives.

Other philosophers take a more nuanced approach. Christine Korsgaard states some animals should have moral status because they value themselves. She is referring to animals with higher intelligence that have a sense of self (e.g. animals that can mourn dead kin), such as dolphins and non-human primates. She also implies other animals, like the blobfish, are not worth our moral consideration. Yet, she maintains that all animals are morally important because they and humans share certain natural capacities that tie us together.

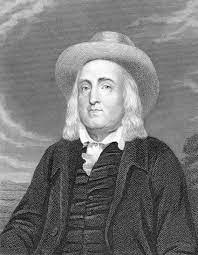

Finally in the pro animal corner, there are a group of philosophers that believe it is morally impermissible to harm or kill animals. Starting with Jeremy Bentham, the father of utilitarianism, he wrote that anything is worthy of moral consideration if it has the capacity to feel pain. If utilitarianism seeks to maximize pleasure and minimize pain, then the pain from harming and killing animals must outweigh the pleasure or benefit we receive from it.

There are some finicky conclusions we can draw given Spock’s “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few” logic though. Bentham would agree that killing one human to give the organs and save five patients is morally right. Extending out, we could say that the torturing and killing of a hundred-thousand animals to create a vaccine that could save billions of humans is not only morally justified, but a moral obligation. There’s an even more obscure edge case known as CIPA disease. CIPA (Congenital Insensitivity to Pain and Anhidrosis) disease is a rare genetic disorder that makes feeling pain and sweating impossible. With this information, it should be morally justifiable to kidnap all of these people and use them for medical testing. They can’t feel physical pain and the mental anguish they receive will always be outweighed by the majority of humans and animals who have benefited from their misfortune.

Peter Singer takes this utilitarian approach and goes in a different direction. He proposes an equal consideration of interests (I will use ECI going forward), which argues that all identical interests should be given equal weight regardless of the living thing(s) affected because of our capacity to feel pain. Put in simpler terms, anything that is wrong to do to humans is equally wrong to do animals. He even takes speciesism and puts a spin on it by juxtaposing it to racism. In the short term it may seem wrong to stop all production of meat in the food industry. The economy will fluctuate wildly, people’s livelihood will be disrupted, and there will be mass protests when people can no longer have bacon or milk chocolate. On the other hand, cows on a farm are reminiscent of African slaves on a plantation. The ending of slavery in the United States caused the economy to fluctuate wildly, disrupted people’s livelihoods, and caused mass protests, but would we go so far as to state that those reasons were enough to continue human slavery?

As compelling as Singer’s argument is, there are again weird situations that seem to invalidate it. Imagine if you, your child, and your pet dog were stuck in a cabin during a blizzard. There is no way to leave the cabin safely, contact people for help, and you are low on provisions and at risk of starving. Would you kill the pet dog to feed your child, or vice versa? Singer would say that in his ECI, it is wrong to kill either the child or the pet. However, as a father, I feel compelled to say that I would do anything to save my son. Thus, I naturally am inclined to think that my son has a greater consideration of interests than any of my pets.

The final philosopher on this list is Tom Regan. He takes Korsgaard’s argument and takes it further by extending the similarities between humans and non-human animals to include more than just natural capacities. All animals have desires, can feel emotions and pain, have expectations, are born and die, and are deserving of a certain standard for their quality of life. Additionally, he takes the argument for marginal cases (i.e. babies, senile grandparents, and people with mental disabilities) and extends that all animals, human and otherwise, must have intrinsic value. It’s normal to think animals have natural value as products for food and items, but also have intrinsic value. So, if we take a comatose human, what value does that human have? They are unable to contribute to society, cannot maintain or create relationships, but we cannot fathom killing them or not providing them medical help. That is because that person has intrinsic value, and deserves proper respect. Because all animals have intrinsic value similar to humans, all animals must also have rights similar to humans. Furthermore, because all animals have rights, it logically concludes that they have moral status.

In conclusion…

So, what is the verdict on non-human animals? I personally believe that it is morally impermissible to harm or kill animals directly (e.g. throwing a kitten into a river). I also believe that it is morally impermissible to harm or kill animals indirectly (e.g. buying a cheeseburger). As much as I love meat, me doing so is immoral because it harms another living thing. However, where I do draw the line is where I’m weighing the lives of humans versus animals, such as medical testing. Personally, I have a son with Addison’s disease. If it wasn’t for the decades of medical testing done on animals, then there is a strong possibility that he would not survive. It’s horrible to say aloud, but I value my son’s life more than the thousands of animals sacrificed to make his future a possibility. Again, this is all my perspective and please post what you think in the comments!

Also here is a list of additional resources I used while making this article:

- Animals and Ethics

- Animal Products and Byproducts

- Animal Rights

- Carl Cohen: Animal Rights

- Ethical Dilemma

- Ethical Theory

- Killing Animals for Food

- Moral Status of Animals

- Non-Human Animals

- Should Animals have Human Rights?

- Should we be Vegeterian?

It is not an act of kindness to treat animals respectfully It is an act of justice.

~ Tom Regan